Ambassador Johan Marais has been a qualified veterinary surgeon for over two decades. He grew up in Etosha, Namibia and on the Highveld of South Africa before becoming a qualified veterinary surgeon in 1991.

From then, Johan spent years in equine racing, before being a senior lecturer, then later head of the Equine Clinic in Pretoria. Johan has been the president for both the South African Equine Veterinary Association and the South African Veterinary Association and acquired a BVSc Honours degree in 2001, and an MSc degree in wildlife in 2007.

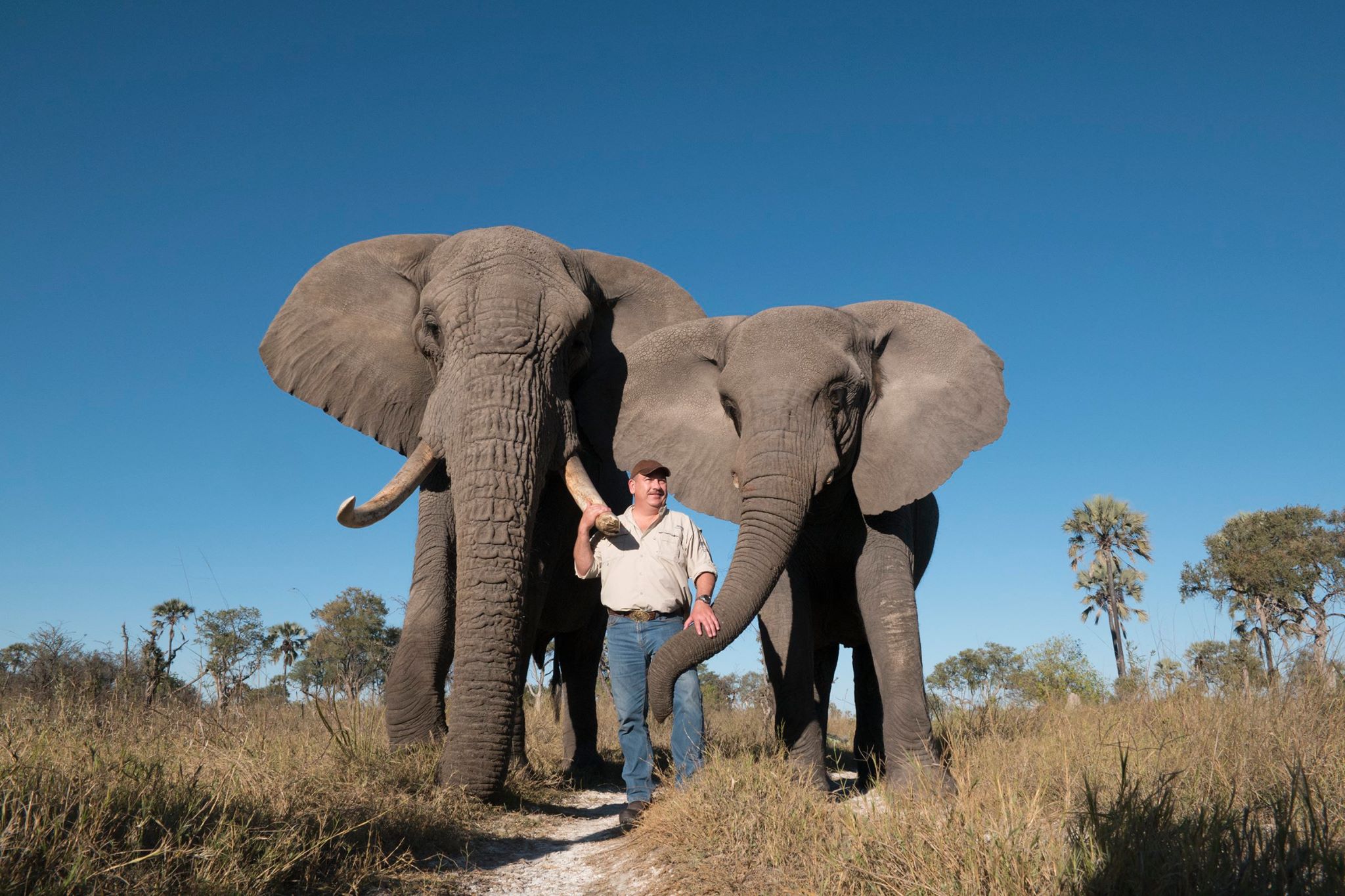

In 2012, Johan founded Saving the Survivors which focuses on looking after endangered wildlife, including Rhinos and Elephants, which have suffered from the effects of poaching. Johan talks about the challenging aspects of conservation and the great team he works with.

Words by Dr Johan Marais, Founder of Saving The Survivors

I am the CEO and one of the veterinarians within Saving The Survivors. I am by trade an equine surgeon, however now I handle all of the rhino poaching cases, as well as surgery on any of the large animals, such as rhino, elephants, giraffes and buffalos.

In 2012 I realised that something needed to be done about the rhino poaching crisis from a veterinary perspective. We were called out to treat a rhino with horrific facial injuries, it was only then I realized there was no published information on how to treat these injuries, as well as the normal anatomy of a rhino. Even to pioneer a basic procedure like the placement of a cast on an adult rhino limb with a severe fracture as a result of a gunshot wound, proved to be challenging and difficult.

Therefore, our nonprofit charity ‘Saving the Survivors’ was born and aimed to provide information and veterinary treatment for rhinos that have been a victim of poaching. We have pioneered the treatment of facial injuries, where the horns have been brutally hacked off.

Since we set up 7 years ago, we have performed several successful world firsts, namely abdominal colic surgery on White rhino and elephant, arthroscopic surgery on White Rhino and the casting of fractured limbs on rhino.

Our main two pillars at STS are first to maintain biodiversity by caring for and rescuing primarily threatened and endangered wildlife species, and secondly by conserving threatened and endangered species in Africa by developing and supporting conservation programmes and projects that threaten biodiversity.

Data shows a sixth mass extinction in Earth’s history is underway and is more severe than previously feared, according to research. Data available for land mammals show that almost half of these have lost 80% of their range in the last century.

To give three examples of iconic species:

a. In the late 1960s, 70 000 Black rhino roamed Africa. In 2019, the numbers are less than 4500.

b. The lion was historically distributed over most of Africa, southern Europe, and the Middle East, all the way to north-western India. Now the vast majority of lion populations are gone.

c. Lastly, a mere 50 years ago, a minimum of 1 million elephants roamed the plains of Africa. Currently, we have less than 400,000 elephants left in Africa.

Regions with an extraordinary richness of life are of particular concern, such as the African continent, which is the last place on Earth with a range of large mammals. A study published last year by IPBES said that the actions of humanity could lead to the extinction of half of African birds and mammals by the end of 2100.

While climate change is a growing threat, the main drivers of biodiversity decline continue to be the loss of natural habitat, and the overexploitation of plants and animals by humans through logging, hunting and fishing.

In the late 1960s, approximately 70 000 Black rhino were present in Africa, while as recently as 2008, the White Rhino population numbered close to 22, 000 animals. The majority (98.8%) of the White rhino occur in just four countries: South Africa, Namibia, Zimbabwe, and Kenya. Currently, there are less than 5 000 Black rhino left in Africa, and approximately only 12 000 to 15 000 White rhino remain.

Saving the Survivors work tirelessly to save injured and poached Black and White rhino in South and East Africa, by forging partnerships with governmental and private stakeholders. STS is also supporting breeding programs of Black rhino in East Africa. While our focus has been mainly on rhino, we are in discussions with several governmental institutions to support them in the fight against poaching. By saving one Black rhino female, which can go on and have 8 more calves in her lifetime, we have saved not only one animal, but eventually 30 to 50 animals from her offspring.

One of the biggest challenges faced is the difficulty to deal with an animal3 to 10 times the size of our domesticated large animals. A wild animal can only be immobilised (and therefore treated) maybe every 3 to 4 weeks. The mere size of the animal pose a great challenge with regards to wound treatment, fracture treatment and our ability to perform diagnostic imaging on them, such as radiographs and ultrasound out in the field.

Being pachyderms with their thick skin makes it challenging when we perform urgent surgery, especially when we are treating injuries such as gunshot wounds.

I often mention to other veterinarians that they have to forget what they were taught about treating horses and cattle, and think out of the box when it comes to treating these large mammals.

The gastrointestinal system of rhino is very close to horses. A 6-month-oldWhite rhino calf was bottle-fed with milk and swallowed the teat by accident. He appeared to be fine for 10 days after which he started to develop colic signs. The veterinarian phoned me and together we decided it would be best to perform the same operation on the little calf than what they regularly do on horses an abdominal colic surgery. It turned out that the teat got stuck in the small intestine just behind the stomach and was causing an obstruction. This area is inaccessible to the surgeon and I had to “milk” the teat to an area of the intestine that we could exteriorize, after which the intestine was cut open and the teat was removed successfully. The intestines were placed back inside, the abdomen and skin closed with strong suture material, and he was left to wake up from his anaesthesia.

The little calf stayed on a drip afterwards for a few hours before he was returned to his owners. He made a speedy recovery and grew up to be a magnificent rhino bull!

www.savingthesurvivors.org